Charlottesville's tree canopy has substantially declined from 2004 to 2018, dropping by an overall 10 percent during this time. What does this mean for Charlottesville's residents?

By 3rd-year student Aayusha Khanal

Though conversations about the weather used to be small talk, it is quickly becoming a hot topic— quite literally. We are experiencing a rise in the average temperature, frequency, and duration of hot days, which can have an adverse impact on communities that do not have enough financial resources or government support for extreme-heat reduction efforts. Tree

canopies are one way to provide relief from the heat. Canopies are the parts of a neighborhood or city that provide shade and help cool down the surrounding air temperature. One study demonstrated that an area (at the scale of an average city block) significantly reduces its daytime temperatures when at least 40 percent of the area is covered by tree canopy. As students, employees, and residents of Charlottesville, we must ensure that the places in which we live, work, and play are sustainable and abundant with trees.

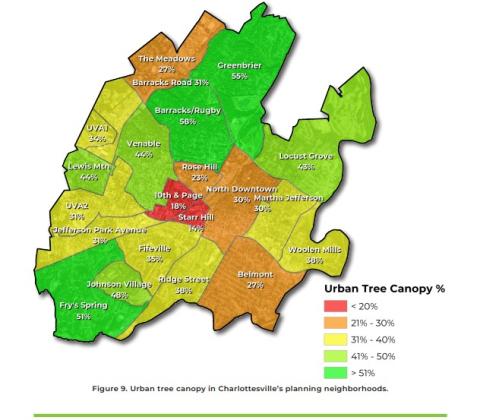

In a recent study conducted by the Charlottesville Tree Commission, the city found that its tree canopy is significantly declining. From 2004 to 2018, total canopy cover dropped from 50 to 40 percent, which is an overwhelming ten percent decrease. This decrease, however, is not evenly felt across Charlottesville. Out of 21 neighborhoods, the two with the

lowest tree canopy are 10th & Page and Starr Hill, which are both historically Black neighborhoods. They have 18 and 14 percent canopy cover, while neighborhoods like Barracks/Rugby and Greenbrier have close to 60 percent.

Decades of racist zoning laws and redlining in Charlottesville have systematically deprived communities of color of having enough tree canopy and proximity to nature in their neighborhoods. The Tree Equity Score map, created by the nonprofit American Forests to measure inequalities of city tree canopy cover, reveals that neighborhoods with predominantly people of color and low-income neighborhoods will have significantly lower coverage than wealthy and majority-white neighborhoods. This is a clear violation of environmental justice.

The impacts of relatively low canopy coverage include greater residential heat exposure, as illustrated in the report by the Charlottesville Urban Heat Watch program. Heat exposure can have severe health impacts, and with climate-induced increases in extreme heat, having enough tree canopy cover is crucial. In fact, one study shows that neighborhoods with more tree cover have better overall health and lower rates of asthma, obesity, and high blood pressure.

The findings from the Charlottesville Tree Commission reveal that 72 percent of the city’s tree canopy is privately-owned while 21 percent is controlled by the City of Charlottesville, meaning that the local government has a smaller scope of impact with its tree canopy. Additionally, it has less jurisdiction in swaying private property owners away from cutting down

trees and instead planting more. Therefore both the private and public sectors must take effective measures to increase the number of trees in Charlottesville by preserving existing trees and planting new ones. More tree canopy will help protect residents from extreme weather conditions, reduce air pollution, and bring down the city’s carbon footprint by sequestering carbon from the atmosphere.

Additionally, it would be in alignment with the City of Charlottesville’s goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 and the University of Virginia’s goal of achieving neutrality by 2030 as outlined in the 2020-2030 UVA Sustainability Plan. By equitably increasing tree canopy across all neighborhoods in Charlottesville, we can build a more climate-resilient city.

Aayusha Khanal (she/her) is a 3rd-year UVA student majoring in Public Policy & Leadership and Global Environments & Sustainability. At the Office for Sustainability, she is a member of the OFS Waste Minimization team and helps achieve zero-waste efforts at UVA.